by nathan thanki

At the end of an unseasonably warm week in Bonn, the sun set on yet another round of UNFCCC (climate change) negotiations. The session, quieter than the end of year COP (Conference of the Parties) jamboree, has only dealt with one negotiating track—the “ADP.” The ADP, or Ad-hoc Working Group on the Durban Platform for Enhanced Action (there’s a reason we use acronyms), is a negotiating process established in 2011 in Durban that is supposed to come to a close before COP21 in 2015, which you should note happens to be in Paris. What exactly the ADP is meant to come to a close with is still a matter of debate among countries and observers. The exact language in the decision (1/CP.17) which mandated these talks is a feat of creative ambiguity: the ADP is meant to conclude with “a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties.” The term “applicable to all” has been subject to much debate, too.

In short, the ADP negotiations have not gone well to date.

Since the first session they have been plagued with seemingly insignificant procedural fights, masking the deep divide over fundamental issues and opinions in the global effort to address and adapt to climate change. The most recent meeting in Warsaw concluded with an hour long “huddle” (a sadly common practice since Durban) rather than a transparent, negotiated process. What the huddle decided was not dramatically new, nor, as it turns out, particularly useful for the urgent action we need to tackle climate change, but it did make one very important word choice—to replace the “nationally determined commitments” that had been in the draft decision with “nationally determined contributions.”

A small change to the casual observer, but in a process where every full-stop and comma are up for interpretation, it was a rather drastic shift in the framing of what countries are actually going to have to do as a result of these all these talks. “Contributions” was settled on as a compromise because certain developed countries did not want to, and never did want to, “commit” to tackling climate change (as pointed out in comments below, we can’t say for certain it was one country over another–they all agreed to this change in the end, and in some ways it could be seen to benefit all major economies even non-A1). Even this week, while the US delegation talked loftily about taking ambitious action, at home Obama is fracking the living daylights out of vast swathes of the country and contemplating passing the Keystone XL pipeline to transport Canada’s tar sands (a carbon “bomb”) to the Gulf oil refineries. The idea behind the “contributions” framing is kind to the United States’ brainchild—a “pledge-and-review” approach whereby Parties decide (“nationally determine”) what emissions reductions they want to do, and hope that the sum of those contributions adds up to enough reductions to stay below the 2 degrees warming goal, which is already a dangerous level of warming. Yet as Bangladeshi negotiator Quamrul Chowdury pointed out early this week, there’s a flaw to this plan: “What happens if the sum of all the contributions doesn’t keep us under 2 degrees?”

Surrounding the “contributions” sentence in the Warsaw decision on the ADP (1/CP.19) was the mandate to “further elaborate elements of a draft text” at this session, meaning that many observers and developing countries expected we would begin dealing with text between now and the next COP in Lima this December. By UNFCCC rules, the final text for agreement has to be tabled 6 months before being signed—so while the likes of Avaaz tell their keyboard warriors that December 2015 is a make or break moment, the deadline is actually June 2015. It’s hard to imagine the rules not being bent slightly to allow some degree of refinement, but the agreement should be more or less there.

With that in mind, the ADP met this week, free from the burden of electing co-chairs or agreeing on an agenda. It is almost two years into its work. And yet it is nearly universally acknowledged (even if only in private for some, like the UNFCCC secretariat) that things are not going in the right direction. The task of getting countries to agree to regulate themselves and each other is close to impossible. For one thing, there is very little trust—how could there be, with revelations confirming that the NSA was spying on everyone at the Copenhagen talks in 2009—and not a lot of political will. Previous years have seen intense bullying—replete with threats of US withdrawing its aid to anyone who opposes it—and all sorts of other dirty tactics such as phone calls to capitals to get negotiators fired. On top of this, add increasing corporate influence over the process, which contributes to the persistence of climate denialism, the distraction and challenge of the global economic crisis, and the rise of anti-environment governments in Canada, Australia, and the UK.

But even with all of the above happenings, the power of institutions and bureaucracies means that the show goes on. In spite of everything going on within its own borders, Ukraine still managed to pull together a submission of views. And so, because this wagon keeps on rolling, we find ourselves in one of the more soulless quarters of Bonn… When the session opened on Monday, a lot of developing countries were quite upset and said so. Their beef was with the co-chairs for their management of the process. As mentioned, the ADP is prone to procedural fights, which seem to be stupid, and are, but which really reflect the core concerns of countries. Basically, the co-chairs scheduled talks as “open-ended consultations” (in too small a room) which, in spite of their pleas for specificity, resulted in somewhat of a talking shop, with countries giving general and vague statements that were entirely predictable: the developed countries with a feigned sense of urgency, the developing countries with a furious sense of desperation.

That the statements and positions are entirely predictable is because they have been largely repeated for around twenty years. This lends support to the dismissive attitude of “governments never get anything right” which drove a lot of good, committed people out of the process, but saying that only masks the fundamental reasons for failure to launch. The developed world has done very little to reduce its own emissions or change unsustainable consumption and production patterns. Despite what the PR machines say, the donors of the developed world (“annex-2” in UNFCCC parlance) have mobilized only the tiniest fraction of the finance and technology they promised to, and even then it turned out to be redirected aid money or loans. Meanwhile, in large swathes of the developing world—including in the so called “emerging economies”—governments still struggle to provide for the basic needs of their populations. The World Bank loans, pushed out the door and pocketed by dictators, are still being repaid by the people.

At the risk of stating the painfully obvious: there is much more underpinning and going on with these negotiations than the top-line messages suggest, and the imbalance of power within them, as exemplified by the history of the Kyoto Protocol, do not lend themselves to a fully open, innovative, problem-solving approach. Such dynamics lend themselves to developing countries digging their heels in, growing somewhat paranoid, while the large and well-resourced delegations of the developed world, along with their think tanks and Southern front groups, manipulate the media and pile the pressure on. This tension erupted in the final days of Durban and the result was the ADP, a product of many years of build-up.

Since Monday the pushback has been coming thick and fast, and the exchanges between the co-chairs and Parties has at times verged on hostile (for diplomatic standards). Ignoring the appeals for a “contact group” to be formed, the co-chairs from Trinidad and Tobago and the EU pushed on with the open consultations. Nauru spoke first to say that the process was wrong—it wasn’t clear what topics they’d be discussing each day. They’d begun with the “adaptation” element, but apparently Nauru was notified only half an hour beforehand. Cuba, no stranger to exclusion from the international community, didn’t like the smaller room because not all countries could sit at the table. When they did get down to more substantive matters, the old divides remained in new arguments. Now the developed countries want “nationally determined contributions” to consist only of mitigation efforts. Given that everyone has to make a “contribution,” this would mean asking the poorest countries on earth, who use and have always used a miniscule sliver of the world’s energy supply, to reduce their (almost non-existent) emissions. Many developing countries want activities under all of the “elements” mandated by the Durban decision—building capacity at home and especially planning and implementing adaptation projects—to count as part of their contributions. It has long been a concern of some civil society groups that the developed country Parties were building a “mitigation only” regime, which they would entice or bully the developing countries into before engineering another “great escape” of their own—as they’ve done with their Kyoto Protocol commitments.

Even ignoring for a moment the injustice of asking all developing countries to “contribute” exclusively via emissions reductions, such action could only ever be undertaken if the money, technology, and capacity was there to do so. As the resources are not there in many developing countries, or are being used for other priorities such as health, education, infrastructure etc., the developed countries have to provide. I’m not just saying that because I think it’s fair: this is all in the Convention. This is all in international environmental law. The Convention is very clear: “The extent to which developing country Parties will effectively implement their commitments […] will depend on the effective implementation by developed country Parties of their commitments […] related to financial resources and transfer of technology and will take fully into account that economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.”

However that hasn’t really happened and all throughout this week we’ve been hearing the now familiar refrain from the “Umbrella Group”—New Zealand, Japan, Australia, US—that finance should absolutely not be included in the “contributions.” Why would we set targets, they ask, in order to meet a goal they set for themselves at COP16 in Cancun to mobilize $100 billion per year by 2020? The common excuse, a bogus one, is that they cannot budget that far ahead, that they cannot get approval from their national parliaments and congresses. The real reason, of course, is a lack of political will. The political will is so stymied that the co-chairs in fact grouped all three of the Durban “elements” that deal with the provision of the means of implementation (finance, technology transfer, and capacity building) as one cluster. This upset most of the developing countries, who repeatedly raised the issue in their interventions throughout the week. Philippines negotiator Bernarditas, who is a thorn in the side of the developed country Parties, stated the resulting effects of this lack of political will: there can be no enhanced action without support. The “Environmental Integrity Group,” and odd grouping of developed and developing countries, did agree with her, but introduced the idea, popular with developed countries, that the donor base should be expanded to include the emerging economies. Again, the Convention is very clear about who is obliged to commit finance (though of course anyone can if they wish): only Parties in annex-2. However, here in Bonn those countries repeatedly demanded that they be allowed to pass off that responsibility to the private sector—accountable to nobody but their shareholders.

Alongside the open-ended consultations, the ADP session this week has also seen a series of technical expert presentations on renewable energy and energy efficiency. The idea was pushed by AOSIS, the Alliance of Small Island States, who are desperate to find solutions to two of the most serious problems they face: climate change and lack of access to energy. The sessions, while a good start, were largely disappointing—basically put on to placate AOSIS—and even included the US attempting to sneak in shale gas as a source of “clean” energy. Almost as bad, the secretariat invited big energy suppliers and the World Bank, who was and is a massive funder of dirty and harmful energy, as presenters. Even the good elements of the presentations—globally funded renewable energy feed in tariffs—have no real way of being made part of the actual negotiations.

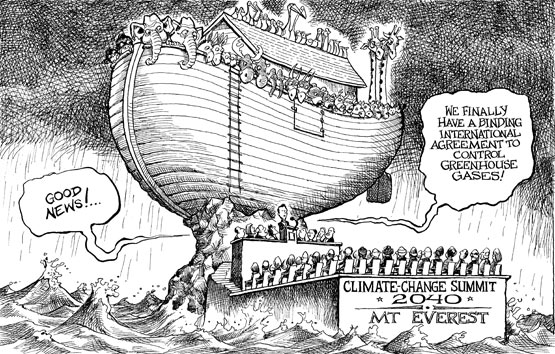

As the closing plenaries wrapped up, the UNFCCC secretariat released a press statement saying that the talks to reach a new agreement were progressing well. While I’m not one to give in to pessimism, such statements are wildly optimistic. It’s a long road to Paris, and it seems we’re walking in circles. The next 20 months could yield yet more road-blocks and dead-ends. Yet for all that, a complete collapse seems unthinkable—actually it seems impossible, given what is at stake for the governments of the world (I don’t mean the climate, I mean their reputations). It is therefore very likely that in order to avoid a Copenhagen style “no deal,” and unable to overcome the differences and obstinacy that prevents a good one, the French Presidency will engineer any kind of deal—even a completely useless one. Their diplomatic efforts to avoid the collapse option—which would really show the world how desperate the situation is—are being fully supported by the UN Secretary General, who has decided to convene a “Climate Summit” of his own in New York this September. The idea to give climate change a higher profile is laudable, and France will use it tactically to get ministers and Heads of State familiar with the issues before COP21, but ultimately it is a massive distraction, a highfalutin show for the cameras, and without any agreed authority.

As we stumble toward Paris, those who have the game rigged have an incentive to make sure everyone else keeps playing. The murmurs in America that Obama can overcome the traditional stalemate of Congress by signing an executive order are repeats of the same murmurs that could be heard ahead of Copenhagen. At best they show the dishonesty of the US delegation’s assertions that Obama has his hands tied at home. At worst, they lead us to believe the lie that Obama will actually act: he is not serious about climate action either domestically or internationally. Most developed world governments are not—and even though governments in the developing world claim to be, they have to deal with the pressing issue of surviving the increasing climate-related disaster before they can fund their own dramatic emissions reductions. The only thing to hijack the apple cart would be massive, strong mobilization in the months and years to come. Social movements, united with progressive governments, or progressive elements within governments, who also have a mandate to stand up to bullying and defend red lines: if these are in chorus, and the red lines being defended are people’s red lines, we can get the best of a bad situation. In Warsaw we said “Volveremos”—we will be back. Now that the eternal talking is back, we need to deliver on this promise.

Nathan: you say that the ‘contribution’ for ‘commitment’ amendment was made ‘because certain developed countries (ahem, the US) did not want to, and never did want to, “commit” to tackling climate change.’ But, according to RTCC:

‘The changes are believed to have been made to accommodate China and India, who were deeply opposed to accept what they see as binding controls on their economies.’**

Which is it?

** http://www.rtcc.org/2013/11/23/un-agrees-on-framework-for-2015-climate-change-deal/

Further to the above, here’s the real problem:

http://www.yaleclimatemediaforum.org/2013/07/global-co2-emissions-increases-dwarf-recent-u-s-reductions/

Hi Robin,

thanks for reading and commenting. I get a lot of “but what about China” talk from Europeans and Americans. Most of the time it is in the spirit of genuine concern at the prospects of a 4 degree warmer world, but sometimes it is malicious, borderline Orientalism, aiming to pass the buck of responsibility (i.e. restrictions) to the emerging (not emerged) superpowers. I’m going to assume the best and place you in the first category.

RTCC have a bias, in my opinion, in that they often just get their quotes from EU spokespeople. Although it is probably true that the Chinese and Indian delegations were not delighted with the wording, because they maintain that there should be a differentiation. They want to say that they will do emissions cuts, but on their own terms, while the developed nations do as they PROMISED in the Convention and Kyoto Protocol, and take the lead in reductions. I think only the most ignorant could say that China and India are comparable in terms of where they are at in their development (human and/or economic) with Europe and the US. Plus, the current level of warming we’re seeing has been caused almost entirely by the US, Canada, EU etc. as they developed. There’s a climate debt that has never been paid. Not to mention the number of people China and India contains…the per capita figures, historical and current, do not make for pleasant reading to Americans.

Seeing as we’re swapping reading lists, I suggest the following: http://www.dhf.uu.se/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/dd61_art12.pdf

http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2014/jan/19/co2-emissions-outsourced-rich-nations-rising-economies

http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1089&context=yhrdlj

But, Nathan, you haven’t answered by question: was the US or China/India responsible for the ‘contribution’ for ‘commitment’ amendment? You seemed certain it was the US – and I was anticipating your confirmation of that, hopefully with evidence. It seemed surprising: the evidence I’d seen was that, leading up to Warsaw, China, India and other developing economies had declared their (understandable) opposition to any commitment to CO2 reduction.

BTW I don’t fall into either of the categories you identify. My interest in the issue is simple: I’m British and I’m anxious to establish the optimum climate policy for the UK, taking account of the harsh realities of international politics.

We’re told that many scientists believe that, if the planet is to avoid dire consequences, it’s essential that worldwide CO2 emissions are substantially reduced and that action to achieve that is urgent – indeed many think it should have started some years ago. Next year in Paris, the UN will hold what’s been described as the ‘make-or-break’ conference: the last opportunity, it seems, to agree to the necessary reductions. And it’s obvious (see for example the graphs to which I provided a link yesterday) that, to be meaningful, such reductions must include reductions by the developing countries – responsible today for 67% of emissions. China alone is responsible for 27%: more than the US and the EU combined.

And the evidence (e.g. the meeting in Bonn last week) is that, for good reason (such as the alleviation of poverty) the major developing economies won’t agree to binding reductions. And, if they don’t, the US won’t. So, with Canada, Russia, Japan and probably Australia also reluctant, all that’s left is the EU (only 10% of emissions). And even that’s showing signs of backtracking, especially in view of events in Ukraine. My conclusion is that there won’t be a binding deal: so we must face the consequences. And the UK should tailor its policies accordingly.

I’m not interested in blame – much (not all) of the data you provided is valid – simply in coming to term with reality.

Nathan: for a more detailed view of my thoughts, you may be interested to see this: http://www.bishop-hill.net/discussion/post/2313902

You’d be welcome to join in.

Hi again Robin,

firstly, apologies for (incorrectly) categorizing you. I was trying to point out that sometimes the questions you were driving at are asked disingenuously by others as a way to justify what would amount to sanctions on economic competitors.

I won’t get into the state of the current British government’s approach to climate change in general (beyond the UNFCCC). It would be too depressing for both of us.

On the 27% emissions: do they account for embedded emissions? It would also be interesting to see a per capita breakdown–my hunch is that there’s a small elite taking up most of the emissions space. Which is the one generalization I’m quite comfortable making, no matter the country. It’s the elites and the corporations they are involved in (which for the most part are based in the developed world) that are historically and currently the largest emitters.

And in terms of “binding,” it comes back to the old saying “form follows function.” The legal nature of the 2015 agreement will depend on its content. It suits a lot of governments to have a “legally binding” agreement with no numbers/targets, and so I’d politely disagree with you and say that we’ll probably get a legal treaty, but with no quantifiable emissions reductions (because it has to be applicable to all). Anyways, whatever legally binding means is lost on me at this point. Remember, the Convention itself is legally binding, yet has not been complied with by any stretch of the imagination.

I’ll check out that link, and how you check out these two. One on climate debt, and one on a fair way to solve this.

http://climate-justice.info/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/EquityVision_v4.pdf

http://www.twnside.org.sg/title2/climate/pdf/climate_justice_briefs/01.Climate.debt.pdf

But, Nathan, you still haven’t answered by question. My view is that, if you can’t back up a claim (in this case that the US was responsible for the ‘contribution’ for ‘commitment’ amendment), it’s best not to make it. Otherwise, it creates doubt about other claims you make.

So, with that in mind, here’s my authority for my claim that China is responsible for 27% of emissions: http://cdiac.ornl.gov/trends/emis/meth_reg.html (Go to “Preliminary 2011 and 2012 Global & National Estimates”.) That’s the best measure we have. You ask if it takes account of ‘embedded emissions’. The answer is no – but, although defining such emissions in very general terms may be relatively easy, trying to measure them in practice, in a way likely to be accepted by all interested parties is horrendously difficult: for example, when China exports goods to the UK, the UK gains but so does China. And how about the massive UK exports to the underdeveloped world in 19th and 20th centuries?

Re per capita breakdown, I’m sure your hunch is accurate – the gap in China between the wealthy middle classes and the very poor is enormous. But China is, quite understandably, trying to close it by massively improving the lot of the poor. That’s one reason why its emissions will continue their massive growth. And on that subject it’s interesting to note that China’s emissions per capita are today pretty well on a par with the EU’s**, creating problems re ‘equity’ etc. (see below).

And on that subject, I’ve read your two links. And they confirm my conviction that’s no prospect of the world coming to an agreement to make the substantial CO2 emission reductions that many scientists say are essential. Just take the first paragraph of the ‘Vision for Equity’: there’s no ‘we’ that can do anything; no major government is likely to agree to ‘transform the system’; there’s no supra-national authority that can enforce things ‘we must do’; there’s no way of defining a ‘global emissions budget’ that would be internationally agreed, let alone a method of enforcing it. In any case, it’s all made hopelessly complicated by the fact that total emissions by the developing world since 1850 are now much the same as those of the developed economies.*** So any attempt to settle matters on the basis of ‘fairness’ or ‘equity’ would be hopelessly difficult.

All this stuff exists in a dream world – we need to wake up to hard practical reality.

** http://www.pbl.nl/sites/default/files/cms/publicaties/pbl-2013-trends-in-global-co2-emissions-2013-report-1148.pdf (see 2.3 on page 15) and http://theenergycollective.com/robertwilson190/329626/new-reality-chinese-capita-carbon-emissions-are-now-same-europes

*** http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/10/31/climate-emissions-idUKL5N0IL47J20131031

Nathan: as I’ve said before, my interest in this is solely in whether or not the drastic and immediate cuts in global CO emissions many scientists say are essential are likely to be achieved. That can happen only if the UN meeting in Paris next year (UNFCCC COP21) succeeds. And remember that aims only for reductions effective from 2020 – many believe that’s too late **.

As I’ve also said, such cuts will be possible only if the Non-Annex I countries (see the UNFCCC Convention), commonly referred to as the ‘developing world’, agree to share in the necessary reduction. After all, they’re responsible for about 70% of current emissions so their participation is essential. Yet my reading of the situation is that, since the Copenhagen debacle, these countries (which BTW include major economies such as China, India, South Korea, Brazil, South Africa, Saudi Arabia and Iran) have been adamant that they will not agree to any reduction commitment. That’s why I was interested in your assertion that it was the US, and not China and India as reported by RTCC, that was responsible for the ‘contribution’ for ‘commitment’ amendment. You went on to claim that the US ‘did not want to, and never did want to, “commit” to tackling climate change’. That may be true. But it’s also, it seems, true of the developing world.

I have no interest in apportioning ‘blame’: both the US and the developing nations have understandable reasons for their position. For example, many of the latter are determined to improve the condition of their very poor. And, according to recent research ***, ‘increases in carbon emissions and economic development is widely recognized as a pathway to improving human well-being.’ As so often, the best example is China: because of affordable, reliable electric power derived from inexpensive fossil fuels, mainly coal, it has lifted about 600 million people out of poverty in the last 30 years ****. It’s hardly surprising it plans to continue with this and that other developing economies are determined to follow its example.

So we face a harsh reality: drastic cuts in emissions are not going to happen. Perhaps our best (only?) hope is that the sceptics are right.

** http://www.theguardian.com/environment/2013/nov/21/world-delay-drastic-emissions-cuts

*** http://www.nature.com/nclimate/journal/v4/n3/full/nclimate2110.html

**** http://www.worldbank.org/en/country/china/overview. (Go to ‘results’) Also see: http://www.iea.org/newsroomandevents/speeches/131206MCMR2013LaunchRemarks.pdf (See the opening paragraph.) This IEA presentation provides a good short overview of the reality of coal’s dominance of power generation worldwide.

I guess hoping that it’s all a bad dream is one approach but I don’t think either you or I, or many people in fact, would settle for it. Especially as IPCC AR5 working group 2 report comes out, showing the full scale of what the impacts will be (and also, where they will be).

So dismissing that, we’re stuck in the UNFCCC mud, the blame game, the “you-go-first” approach. I am a little less reluctant to apportion blame. I’d rather find solutions, of course, but ignoring who is to blame is important. The blog will be edited to remove the snarky reference to the US. Nobody outside of that huddle in Warsaw can definitively prove who forced the commitments-contributions transformation, and anyway all Parties agreed to it, so technically they are all to blame (although we can safely say some were bullied into it).

“You went on to claim that the US ‘did not want to, and never did want to, “commit” to tackling climate change’. That may be true. But it’s also, it seems, true of the developing world.” I agree it seems that way. They don’t want to commit to the reductions in the same legal way as the US should have to, but they do want to do the reductions. Does that make sense? They want to transform their own economies on their own terms. Probably the IMF loan experiences influence that stance.

“Drastic cuts are not going to happen.” I am as cynical about this prospect as that conclusion. But I refuse to accept it. Maybe that’s youthful belligerence. I don’t care (part of being young and belligerent).

But I hope the above edits are satisfactory?

Nathan: you ask if your edits are satisfactory. Well, yes – except that you still claim the commitments to contributions amendment was made ‘because certain developed countries did not want to, and never did want to, “commit” to tackling climate change’. How can you be so sure it was developed countries? After all, in total contrast, here’s how RTCC reported it **:

QUOTE

The word “commitment” changed to “contributions, without prejudice to the legal nature”, while “those in a position” to make commitments was changed to “those who are ready”.

The changes are believed to have been made to accommodate China and India, who were deeply opposed to accept what they see as binding controls on their economies.

UNQUOTE

I believe that, unless you had some key inside information, you should have been neutral on this issue. I say that because it’s not unlikely that this wording could contribute to the destruction of hopes of substantial emission reduction. To apportion blame now without any evidence (you even accept that nobody outside the huddle knows what happened) could be regarded as irresponsible.

In any case, there’s a wealth of evidence that China and India are determined not to be tied to commitment. And for good reason: see the research re poverty alleviation I cited in my preceding post. Here, for example, is the opening paragraph of a pre-Warsaw article in ‘The Hindu’ ***:

QUOTE

India, China and other countries in the Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDC) group on Tuesday took the position formally that the new climate agreement must not force developing countries to review their volunteered emission reduction targets. Setting themselves up in a direct confrontation with the developed countries, the LMDC made it clear that it was not in favour of doing away with the current differentiation between developing and developed countries when it came to taking responsibility for climate action.

UNQUOTE

A change from ‘commitment’ to ‘contribution’ would be wholly in keeping with such sentiments. So, very frankly, I cannot agree with you: it does seem that the larger developing economies don’t ‘want to do the reductions’ – certainly not yet. And, if they won’t, the US won’t.

I’m jealous that you’re young and belligerent: see my pic – although being old doesn’t stop me from being belligerent. But, whatever your age, refusal to face up to probable reality is not usually a good way of tackling a problem.

** http://www.rtcc.org/2013/11/23/un-agrees-on-framework-for-2015-climate-change-deal/

*** http://www.thehindu.com/opinion/editorial/a-crucial-milestone/article5344195.ece?ref=relatedNews#comments

I am not objective — nobody is. The history of the negotiations are ample evidence of developed countries, with the US front and centre, stalling action on climate change. The new tactic now that the world realises climate change is here (even if most people aren’t savvy to the true horrors of the coming impacts) is to shift the blame and responsibility.

In Warsaw, the huddle came at the end of a week of talking. You need to recall what happened in that week. I jogged my memory with TWNs update — http://www.twnside.org.sg/title2/climate/news/warsaw01/TWN_update24.pdf — and it shows that India was happy to have “commitments” in the text, so long as there was reference to differentiation (they wanted to say “in accordance with Article 4 of the Convention”). Those opposed to differentiation (yes, the US) refused. The compromise was “contributions.” When I get time I’ll edit again to reflect exactly that.

I don’t quite understand you. You want to say that we’re fucked, but are not interested in blame. Ok, so we’re fucked. Now what? I have to live another 60 odd years on this Earth. I’m not just sitting back and accepting catastrophe, even if it may be inevitable. And I am not going to sit back and accept injustice, with or without a backdrop of collapse.

An interesting view, Nathan. Some comments:

1. Here (**) are some graphical data on global CO2 emissions. The first thing to note is that the EU is today emitting less than it did 30 years ago and the US about the same as then. Both show a slight downturn in recent years. China, India and the other Non-OECD countries (i.e. the developing world) are however emitting massively more; and that growth is accelerating. So, however you look at it, unless that acceleration is reversed, the big reduction in emissions that many scientists say is essential to avoid catastrophe isn’t going to happen. Therefore, it’s essential that China, India etc. make reductions now: the US and Europe cannot do it alone. (For more detail, this interactive graph (***) is interesting.)

2. Yet the evidence is that the developing countries have no plans to reduce emissions now. (I don’t blame them BTW – as I’ve said several times above, they have good reason for this, not least the alleviation of poverty.) So, when, as it did, India insists on ‘differentiation’ in accordance with Article 4 of UNFCCC, it’s effectively excluding any obligation to reduce emissions: that’s what ‘differentiation’ in this context means. The Convention was agreed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992 and the world was divided into two blocs: Annex I (the developed economies) and Non-Annex I (the least developed world, OPEC members and developing economies). The former were to be obliged to commit to GHG emission stabilization. The latter were not. But, in those days, Non-Annex I countries were responsible for only about 30% of emissions. Today that’s nearly 70%. (**) But the categorisation hasn’t changed and, in citing the ‘common but differentiated responsibilities’ principle, the Non-Annex I countries have resolutely refused to change it (****). India was simply confirming that position. That’s why the US rejected it – not unreasonably it considers it an outdated concept in 2014. Here’s a report (*****) of an interview with the leader of China’s delegation in Warsaw:

‘… Xie Zhenhua said that he was not in Warsaw to rewrite the content of the original framework, which should be adhered to in the new agreement. “We are very strong on this point,” he said. “On terms of joint effort, there should be no differentiation, but in terms of targets there should be.” He stressed that China was a victim of climate change, and that its increased emissions was inevitable as the country goes through necessary industrialisation as it develops.’

Note that last phrase: “its increased emissions was inevitable”. Or consider this extract from a report (******) on negotiations in Bonn last year:

‘Chinese chief negotiator Su Wei also said China could not impose caps on its rising emissions because it needed time to focus on economic growth, despite U.S. calls for tougher action by Beijing.’

Nathan: surely you must agree that Xie Zhenhua’s and Su Wei’s comments couldn’t be plainer: China has no intention of reducing its emissions. And, if China won’t, the US won’t – i.e. it’s a Mexican standoff. Apportioning blame, as you seem determined to do, is pointless.

3. Action on climate change is stalling because of that standoff. Yet you say there’s ‘ample evidence of developed countries’ are responsible. I’d be grateful if you’d provide a few examples of that evidence. Thanks.

PS: you criticise me for refusing to apportion blame. Why? Whatever benefit comes from apportioning blame? If you like, I’ll expand on this later. As for ‘injustice’, that’s another fascinating topic for later – if you’re so minded.

** http://www.yaleclimatemediaforum.org/2013/07/global-co2-emissions-increases-dwarf-recent-u-s-reductions/

*** http://tiny.cc/u5agdxhttp://tiny.cc/u5agdx

**** http://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/environment/global-warming/Nations-will-face-big-political-question-in-Lima-over-climate-change/articleshow/30067574.cms

***** http://www.rtcc.org/2013/11/20/divide-between-rich-and-poor-at-un-climate-talks-as-wide-as-ever/

****** http://in.reuters.com/article/2013/05/03/climate-talks-idINDEE9420DM20130503

My second link above may not work. Here’s the full URL: http://www.google.com/publicdata/explore?ds=d5bncppjof8f9_&met_y=en_atm_co2e_pc&idim=country:CHN&dl=en&hl=en&q=china+co2+emissions#!ctype=l&strail=false&bcs=d&nselm=h&met_y=greenhouse_gas_emissions_co2_equivalent&fdim_y=greenhouse_gas:1&scale_y=lin&ind_y=false&rdim=region&idim=country:CHN:USA:IND:GBR:DEU:JPN&ifdim=region&tdim=true&hl=en_US&dl=en&ind=false

Nathan: my post dated March 28 is still ‘awaiting moderation’. What happened?

Robin,

apologies for the few days delay — we’re very busy.

This refers to the UK – but is relevant to the US also: http://ipccreport.files.wordpress.com/2014/04/uk-climate-policies-are-pointless2.pdf

Just play around with the data on this: http://www.gdrights.org/calculator/#

Nobody should really be patting the EU on the back for emitting less than it did 30 years ago, it’s not in line with their responsibility, so they are failing, then end. It’s like telling an alcoholic that they’re doing great for only getting blackout 6 days a week instead of 7 like they used to, they’re still getting black out and making a mess for everyone. Nearly no countries are without blame for fossil fuel emissions. Some are more to blame than others, while some are easier to blame than others, who you choose to target says pretty much everything about your character.

The main reason the EU has (slightly) reduced its emissions is the effect of the economic recession. And that’s no reason for, as you put it, patting them on the back. As for blame – see my comments elsewhere. Best not to target anyone.

Great and interesting discussion a couple of thoughts:

1. Yes the South has greater current emissions – they are also 6-7 times as many people so not really shocking. And of course when we’re talking about fitting into an emissions budget we have to talk about that budget over the whole time (i.e. since 1850) and when we do that the South’s shares, particularly per capita, are drastically less than the North’s. So that’s why “blame” matters – how can you say you want to solve a problem if you don’t consider the background/context to that problem (i.e. the South only have to limit their emissions today because the North got rich by never having a limit.)

2. It doesn’t seem correct to say ” Yet the evidence is that the developing countries have no plans to reduce emissions now” – there is plenty of evidence. See this paper based on a Stockholm Environment Institute study which shows the pledges of non-Annex I prior to 2020 will achieve MORE abatement than those of Annex 1. http://climate-justice.info/wp-content/uploads/2011/12/Durban-Digest_Pledges_NH_hi-res.pdf

3. So then there seems to be two questions:

a) Is this enough, what they are promising to do? Well according to analysis by EcoEquity with their Greenhouse Development Rights’ calculator – for many of those countries (e.g. China) their promise actually does align with what you would call a ‘fair’ share – given their historical responsibility and capacity. IN the case neither of these is necessarily negligible but then, neither is their promised cut.

The issue is that we actually need China to do more than its fair share if we’re to keep warming from becoming too dangerous (I never know how to phrase this… to avoid run-away climate change is really what I’m most scared about but I don’t want to minimise the devastating impacts that will happen before that too). But why/how would China do more than its fair share if the richest and most powerful country in the history of the world has never even got to close to its fair share? Or when the so called climate ‘leaders’ in Europe have also failed to grapple with what their responsibility entails and currently have the position that they will NOT reduce emissions between now and 2020 (they are already at their 2020 goal)?? The only way the South CAN and will WANT To take on this effort if it’s supported to do so… so until there’s a commitment to finance to meet the scale of the challenge and a massive shake up of intellectual property controls, to be blunt, it looks like the North saying: do as I say, not as I do or have done for the last 250 years.

b) Why doesn’t the South (or some part of it) want to have a legal form that appears stricter… well as Nathan pointed out they are not opposed to the word ‘commitment’ per se, but were concerned about it in a context which didn’t differentiate between countries. And given that when Canada broke its internationally legally binding commitment to meet its QELRC under the Kyoto Protocol, or when Russia and Japan walked away from the commitment to negotiate a second and subsequent commitment period of the Kyoto Protocol they suffered no consequence I can see why the South might be worried – because it’s easier to punish them. States are not equal in the international system and international law is frequently used by the North to discipline the South – in the specific case of the UNFCCC it’s pretty easy to imagine that ‘non compliance’ by a Southern country would lead to them being excluded from the finance and technology transfer that the North owes them for their climate debt… so why should those who have not caused climate change sign up to a scheme where the polluters always get off scot-free but they may have to pay a price?

To clarify – I think all countries should be bound – but given past behaviour (across many regimes, e.g. the WTO) I can understand why some are reticent.

A interesting contribution, alex, to an important discussion. Thanks.

Some comments:

1. As I’ve said above, my concern in this thread is solely in the critically important question as to whether or not there is any likelihood that the world will achieve the drastic and immediate cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions that many scientists say are essential if we are to avoid serious consequences. BTW, I say “immediate” although the best we can now expect is agreement in Paris in 2015, effective 2020. So – are we likely to achieve even that?

2. For the reasons I’ve set out in detail above (and touch on below), I believe we are most unlikely to achieve it. If I’m right, that’s an important finding – the focus now should be on facing up to that reality and its consequences. And, given that harsh reality, attempts to apportion blame are pointless – unless there is any prospect that such a complex and controversial exercise could be completed in time to effect what happens in December 2015. There’s obviously no such prospect.

3. Nonetheless I agree that questions of blame and justice are important and interesting. But I suggest they be discussed in a different thread. Nathan: any chance of making that possible?

4. I wholly agree with you that the developing economies’ greater emissions are “not really shocking” in view of their many more people. (BTW I prefer “developing economies” to “South” which is not much used these days and to “Non-Annex I countries” which is too technical.) And, even though the developing economies have emitted about half of all emissions since the Industrial Revolution**, that’s not shocking either, or even surprising – because (a) they’re (ahem) developing and (b) they have vastly more people. Nor is it surprising that they’re not really interested in limiting emissions: they’re determined to continue their economic and political growth. And, so long as burning fossil fuels is the cheapest and easiest way of achieving that, they’ll continue to burn fossil fuels – and, in the process, they’ll continue to lift millions of people out of poverty.

5. The evidence you provide about developing countries’ plans for emission reduction is misleading – as well as out of date. Take the most recent UNEP study.*** It paints a bleak picture. Moreover, it doesn’t take much careful analysis of this report to see that matters are really even worse than it states. Thus it talks of the (huge) gap between what’s needed and what’s expected if “pledges” are met – but “pledges” are defined in the vaguest way. Take China for example. The best it can say is that from “a review of available evidence” China “appears” to be “on track” to meet its “pledges”. But note: (1) those pledges are not binding (see my comments elsewhere in this thread) and in particular (2) they’re for reduction in “intensity”, not reduction in emissions. With a fast growing economy, reduction in intensity (i.e. reduction in emissions per dollar of economic output) still allows overall emissions to rise.**** The same “pledges” are made, incidentally, by India. And, if you examine the report in more detail, you’ll find that, apart (just perhaps) from Mexico, no major developing country (say over 1% of global emissions) targets any reduction in its emissions. That’s the reality.

6. So your two questions:

a) As noted above, the developing world is not (for the very best of reasons) promising any emission cuts. For all I know, that may be “fair” – but fairness won’t make global reductions happen. Nor, of course, is the US – for reasons of international power politics, there’s no prospect of Congress agreeing to substantial cuts if China doesn’t. And China has made it clear (see my earlier observations – especially re Xie Zhenhua’s and Su Wei’s comments) that it has no intention of making cuts anyway; and that’s not because the US won’t, but because it’s determined to continue its economic growth. So, as I pointed out to Nathan, we have a classic Mexican standoff. Moreover, the West has almost unbelievably massive debts so cannot possibly provide the finance you say is needed. To think otherwise is to inhabit dreamland.

b) As for the weakness of so-called international law, you’re dead right. Whatever may be agreed, there’s no way of enforcing it – although you may be right that the weaker developing nations may have rather more to fear than most. But I’d be interested to know how you think anyone could punish China – send a gunboat up the Yangtze?

My conclusion? There’s no prospect that the world will achieve the drastic and immediate cuts in global greenhouse gas emissions that many scientists say are essential to avoid serious consequences. We’d better get used to it.

** http://uk.reuters.com/article/2013/10/31/climate-emissions-idUKL5N0IL47J20131031

*** http://www.unep.org/publications/ebooks/emissionsgapreport2013/portals/50188/EmissionsGapReport%202013_high-res.pdf

**** http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-06-04/china-sticks-to-carbon-intensity-target-while-dismissing-co2-cap.html.

How many tonnes of CO2 is the developing word ‘owed’ by the developed? How many years of unfettered development are they entitled to? Is China due the equivalent years from when it became communist? Should it aspire to EU levels of prosperity or US levels? Would Europe and Japan get an allowance because of the after effects of the World Wars and because Europe never had US levels of emissions can they ease off on reductions? Would former Soviet EU countries get the same allowance as China, minus the years since the Berlin Wall fell? If a country has a lot of land per capita does it get to count its natural CO2 reduction as part of its emissions calculation? If a country has a high birth rate should it be penalised for increasing its overall emissions while not necessarily increasing per capita output?

Do you think the public of any developed country would accept future inequality to recompense for any historic disparity between the success of nations? Do national leaders have the mandates to commit their people to these targets? Do you think the public would keep leaders who try to impose significant unilateral restrictions? Without even discussing these questions with their public are politicians just wasting energy going to these conferences?

These questions are not about race. CO2 doesn’t respect national boundaries, it doesn’t remember history and it cares nothing about fairness.

I’ve nothing to add to the above – except to thank Nathan for hosting an interesting – and challenging – exchange of views.